Not Bhabanipur, not Nandigram: Why Suvendu must contest from Nabadwip in 2026 Bengal Assembly polls

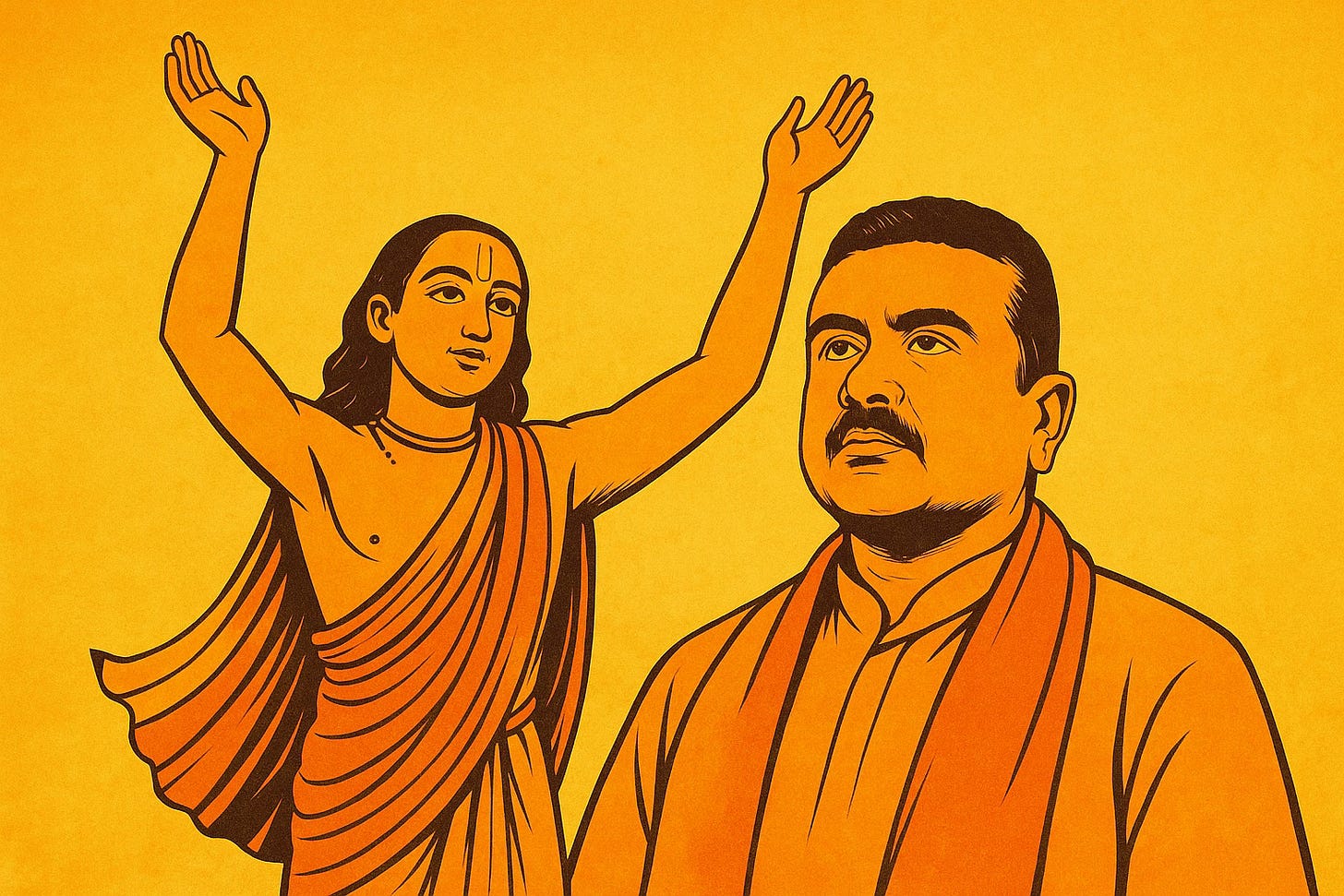

The BJP’s political idiom in the upcoming election in the eastern state should be more Vaishnava than Shakti, with the ‘Hare Krishna Hare Ram’ chant playing a pivotal role.

In an October Kolkata rally held by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to protest against what they alleged was a Trinamool Congress (TMC)-backed mob attack on BJP MP Khagen Murmu, West Bengal’s Leader of the Opposition Suvendu Adhikari asserted, ‘The BJP will defeat her (Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee) in Bhabanipur (in the 2026 Assembly polls). I defeated you in Nandigram, and now the BJP will defeat you in Bhabanipur. We will defeat her by 20,000 votes.’

How will the saffron party bring about such a giant-killing performance in a constituency where the feisty TMC supremo was born, brought up and has politically anchored herself in? Suvendu, who had dramatically defeated her in the 2021 Assembly polls in Nandigram, said, ‘After the SIR (the special intensive revision of the electoral rolls in Bengal), we will ensure her defeat. We will make you a former chief minister…. Out of eight wards in Bhabanipur, the BJP got the lead in five wards (in the 2024 Lok Sabha election).’

If you are a close watcher of Bengal politics, you would know that Suvendu has focused a portion of his energies—verbally, organisationally and operationally—on Bhabanipur for quite some time now. The logic seems sound: if the chief minister can be shown to be in danger of losing her own seat, it would considerably dent the morale of TMC workers and voters, forcing the state’s ruling party into a defensive posture and thus making them over-invest in a single constituency. At the same time, Bhabanipur offers Suvendu a symbolic battleground that reinforces his leadership profile: he would be an even stronger claimant for the chief ministerial post should the BJP wrest Bengal from the TMC next year.

Yet this does not mean that Suvendu himself should contest from the seat, even though there is an obvious buzz within the BJP that he might. Suvendu may or may not directly defeat Mamata in Bhabanipur, but that is not the point here. The point is the wider implication of the choice of his constituency, for the symbolic significance of the seat picked by the BJP’s tallest Bengal leader is crucial as to the whole state, and that symbolism cannot be reduced merely to challenging the chief minister, especially in a seat that is an ideological territory for the state’s ruling party.

Bhabanipur—the secularised Shakti citadel of TMC

At a July event held to anoint Samik Bhattacharya as the new Bengal BJP president, a large photograph of the Kalighat Temple’s Kali idol dominated the stage backdrop and drew the attention of everyone. Later that month in a rally in Durgapur, Prime Minister Narendra Modi followed the customary Hindutva slogan of ‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai’ with chants of ‘Jai Ma Durga’ and ‘Jai Ma Kali’. In fact, the BJP’s official invitation for this programme carried the very words ‘Jai Ma Durga’ and ‘Jai Ma Kali’ in print. The BJP’s aim here was obvious: to localise its Ram-centric political idiom by drawing upon Bengal’s Shakti tradition—the deep-rooted veneration of divine feminine power expressed through Durga, Kali and other feminine deities—and therefore effectively neutralise the accusation of being ‘outsiders’. But the BJP had another key objective in this Shakti outreach: to invade the symbolic space that the TMC had long dominated through its cultivation of a very particular persona of Mamata Banerjee.

The TMC has, over the years, built a mythic aura around Mamata by turning her into a secularised living embodiment of Bengal’s Shakti tradition. The party has built a political theology in which the chief minister is the secular-goddess Ma (mother)—protector, provider, sufferer, sacrificer and avenger. As protector, she is presented as the figure who shields Bengal from ‘outsiders’; as provider, she is portrayed as the source of state welfare provisions; as sufferer, her injuries are invoked as proof of her endurance; as sacrificer, her austere lifestyle is offered as evidence of self-denial; and as avenger, her aggressive words are framed as justified acts of retribution by Ma against those who wrong Mati (soil) and Manush (people). And this political theology is anchored in Bhabanipur, a constituency which houses not only the Kalighat Temple but also Mamata’s modest ancestral home, where she continues to live long after becoming chief minister and devoutly observes her family’s traditional Kali Puja every year.

Can the BJP, then, break the TMC’s monopoly over Shakti-messaging through its own Shakti outreach? Partially yes, but in no way substantially. In an earlier article, I had explained that it is not prudent for the BJP to build an electoral campaign around the ‘Sonar Bangla’ slogan because this ethnolinguistic cultural trope belongs firmly within the TMC’s ideological universe. While Kali and Durga are civilisational entities, even in their case, the TMC has emerged as the emotional owner, having meticulously crafted over time the image of Mamata Banerjee as the secular Shakti incarnate. In addition, the fact that the BJP’s political idiom is centred around a Vaishnava deity and that the Bengal BJP has no female leader who can inhabit the Shakti persona as powerfully as Mamata means only one thing: the BJP can nibble at the margins of TMC’s Shakti-messaging, but never dent its core.

Nandigram’s unsuitability as Suvendu’s constituency in 2026

If Bhabanipur is so central to Mamata’s political identity, why did she go all the way to Nandigram to challenge Suvendu in the 2021 Assembly election? The answer begins with a simple calculation: although Bhabanipur’s demography, comprising large segments of urban, middle-class and non-Bengali voters, somewhat suits the BJP (as reflected in the party’s strong showing there in the 2024 Lok Sabha polls), the party in 2021 did not have a single Kolkata-based leader with enough political capital to convince the Bengal populace that the seat could actually flip in a scenario where Mamata was not contesting. With her Shakti fortress thus firmly secure in public perception, the TMC matriarch felt free to march into Nandigram, a place that was the epicentre of the 2007 anti-land acquisition movement that had propelled her to power in 2011, a place situated in the Adhikari family’s traditional stronghold Purba Medinipur district, a place where the electorate was largely rural with a relatively higher Muslim voter share than Bhabanipur.

Analysts cite multiple ways in which this audacious move helped Mamata retain the CM chair despite narrowly losing in the constituency: it burnished her image as a fearless fighter willing to give up a safe seat; it tied down Suvendu’s time, attention and resources within Nandigram; and it galvanised the TMC cadre across the entire state of West Bengal. Yet, in my view, the most damaging impact on the BJP was something deeper: Mamata’s move partly resurrected the 2007 anti-land acquisition movement narrative, an issue in which the BJP had no real role, no emotional claim, no ideological resonance. While Suvendu’s bitter personal battle with Mamata over ‘who owns the Nandigram legacy’ considerably boosted his own political stature (thanks to his win), it ultimately looked like a colossal waste of his political capital on a topic that added zero value to—and in fact diluted—the BJP’s larger narrative regarding Hindutva, law and order, clean governance and development.

Moreover, Nandigram’s centrality in the media narrative gave the Left unnecessary visibility, and a repetition of this in 2026 could hurt the BJP in several constituencies through the division of anti-TMC Hindu votes. Indeed, the Left leader Minakshi Mukherjee would not be nearly as prominent today had she not garnered media attention by contesting against Mamata and Suvendu in Nandigram in 2021. The BJP must understand one thing clearly: the anti-land acquisition movement narrative can have only the TMC or the Left as heroes or villains. The saffron party are quintessential outsiders in this story, and they must not elevate the story by having their most charismatic leader contest from the seat which is the very landscape where the story is rooted.

BJP’s story is not Nandigram, but Ram

In the July Durgapur rally mentioned earlier in this piece, Modi did not merely chant ‘Jai Ma Durga’ and ‘Jai Ma Kali’—he conspicuously left out the BJP’s signature ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogan. It was pretty clear that the party had felt stung by the TMC ecosystem’s constant portrayal of Ram as a patriarchal deity of North Indian outsiders, alien to Bengal’s refined culture known for its Shakti veneration. The TMC looked at the BJP’s retreat from Ram in Bengal as an ideological victory. Party spokesperson Kunal Ghosh said, ‘The prime minister says he wants development. But what does development mean? It means Mamata Banerjee and her government—Ma, Mati, Manush. It was there, it is there and it will remain. But what has changed? PM Modi. Earlier it was Jai Shri Ram. Now it has become Jai Ma Kali. Has PM Modi changed so much? They used to say Mamata Banerjee does not celebrate Durga Puja. Now, 11 years after becoming PM, Bengal has changed him.’ Ghosh further gloated, ‘Today, one good thing we observed was that “Jai Shri Ram” was not uttered even once.’

Ghosh was not incorrect when he portrayed Modi’s reluctance to invoke Ram as ideological surrender to the TMC. After all, since the days of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, the sociopolitical imagination of the BJP has consistently revolved around Maryada Purushottam. And this symbolic alignment contributed to the rise of the BJP in Bengal no less than other factors such as Modi’s clean image or the party’s narrative concerning economic development. Ram may not be directly worshipped widely in Bengal, but He is present everywhere in Bengal’s civilisational canvas, including nomenclature, literature, devotional traditions, philosophy, visual and performing arts. It is true that in the 2021 Assembly polls the BJP was not perfect in terms of tapping into Bengal’s Ram heritage. But that does not mean that they should be deracinated in their 2026 campaign and end up being desperate imitators of West Bengal’s ruling party.

Don’t discard Ram, but connect him to Krishna

Unlike today, direct worship of Ram had a considerable presence in Bengal in the medieval period. For example, Murari Gupta, a close associate of the medieval Bengali Hindu saint Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, is celebrated within the Krishna-centric Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition (founded by Chaitanya) for his unwavering devotion to Ramachandra. A famous episode within the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition tells us how agonised Murari was when Chaitanya—seeking to test his loyalty to Ram—asked him to give up Ram and worship Krishna. Seeing Murari’s anguish and refusal to turn away from Ram, Chaitanya praised his steadfastness and affirmed his eternal devotion to Maryada Purushottam.

This anecdote highlights the theological significance of Ramachandra in the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition. Even though Chaitanya’s own bhakti (devotion) focused on Krishna and his consort Radha, he worshipped Ram, extolled His virtues as Maryada Purushottam (the best among men—one who always acts within the bounds of dharma) and fully validated Ram-bhakti (devotion to Ram) within the devotional movement he led. Consider the Mahamantra—scripturally rooted in the Kali-Santarana Upanishad—that is the very core of Gaudiya Vaishnavism:

Hare Krishna Hare Krishna

Krishna Krishna Hare Hare

Hare Rama Hare Rama

Rama Rama Hare Hare

Of course, Gaudiya Vaishnava monks understand the Mahamantra (the great mantra) in a Krishna-centric way: they read ‘Rama’ primarily as Radha-ramana, that is, Krishna as the giver of bliss to Radha. But they still honour Ramachandra and they accept that the word ‘Rama’ in the Mahamantra can be legitimately understood as him in a secondary sense. Indeed, many Gaudiya Vaishnavas and most Bengali Hindus outside the sect naturally think of Ram of Ayodhya when they hear or utter the word ‘Rama’ as part of the Mahamantra. And that is why I think that this chant, in a shortened form, and the land where the chant is devotionally rooted, can be the civilisational conduit through which the BJP can reach deep into the Bengali Hindu heart.

Nabadwip could be to Suvendu in 2026 what Varanasi was to Modi in 2014

When Modi chose to contest from Varanasi in the 2014 Lok Sabha election, he did not do it because the seat was the safest for him. It clearly wasn’t, as seen in his decision to contest from a second seat (Vadodara) in his home state Gujarat in 2014 and also the significant narrowing of his victory margin in the seat in 2024. But he still chose to contest there in 2014, for it combined unmatched civilisational symbolism—Varanasi being India’s spiritual capital—with the strategic necessity of creating a decisive electoral wave in Uttar Pradesh, the state where it is located and which sends the largest number of MPs to the Lok Sabha. Of course, Bengal does not have a single, uncontested spiritual capital in the way Varanasi functions for India. Yet Nabadwip comes closest to being Bengal’s Varanasi, combining Sanskrit scholasticism, mass devotion and sacred geography like no other city in Bengal. Even before the emergence of Chaitanya, medieval Nabadwip was famous as a centre of Sanskrit learning in general and the Navya Nyaya school of logic in particular. With Chaitanya’s movement, Nabadwip ceased to be just a land of elite scholasticism—it was now a centre of lived Hindu spirituality expressed through a mass devotional culture that had begun changing Bengal’s religious landscape forever.

But beyond this, perhaps the most significant similarity that Nabadwip shares with Varanasi—with regard to the aim of this article—is the fact that the entire area of the city, uniquely in the state of West Bengal, is considered to be a single, expansive holy place by at least one major Hindu devotional tradition. Gaudiya Vaishnavas refer to Nabadwip as dhama (abode of god), for it was the birthplace and the site of the early lilas (divine pastimes) of Chaitanya, the tradition’s founder whom they consider to be an incarnation of Krishna. The followers of the tradition, in fact, see Nabadwip as non-different from Vrindavan (the place of Krishna’s childhood lilas) in tattva (essence). The city area is theologically conceptualised in the Saraswat lineage of Gaudiya Vaishnavism as a lotus flower made of nine islands (nava-dvipa), with each island corresponding to one of the nine processes of devotion (bhakti).

If Suvendu roots his 2026 Vidhan Sabha election in this sacred geography and the ‘Hare Krishna Hare Ram’ chant, it allows the state BJP to anchor its campaign in a terrain and idiom where it enjoys both civilisational legitimacy and narrative sovereignty. Furthermore, just as Modi’s 2014 Varanasi candidature helped the saffron party sweep Uttar Pradesh, Suvendu contesting the election from Nabadwip could have a strong ripple effect on the Matua belt—the south-eastern region of West Bengal where the Matuas, a Vaishnava socioreligious group largely composed of Namasudra (a Dalit community) refugees from what is now Bangladesh, hold electoral sway. Since the 2019 Lok Sabha election, a large section of this Hari-worshipping community has supported the BJP, drawn by the party’s assurance of citizenship security through the Citizenship Amendment Act. The TMC, once the primary recipient of Matua support, has sought to restore its earlier standing in the community by attacking the ongoing SIR in Bengal as a disenfranchising threat to them. Amidst this turmoil, a Suvendu ticket from Nabadwip—revered by many Matuas as sacred Vaishnava geography—would boost the BJP’s effort to turn the Matua question from one of political apathy to that of civilisational solidarity.

But then, is Nabadwip demographically suitable for the BJP’s de facto chief ministerial face? As per data from Chanakyya.com, Muslims make up 19.9% of Nabadwip’s electorate—a share lower than in Bhabanipur (21.8%) and Nandigram (23.6%). Of course, this by itself doesn’t make Nabadwip an arithmetically ideal seat for Suvendu. There are constituencies that are demographically more reassuring for West Bengal’s Leader of the Opposition. But if you are someone aspiring to lead a state like West Bengal, arithmetic should scarcely be your foremost concern when it comes to settling the consequential question of where you should contest the election. Even Modi’s choice of Varanasi, or Mamata’s choice of Bhabanipur or Nandigram, was not guided primarily by numbers. Their constituencies were chosen to amplify the larger story their parties sought to narrate—nationally, in Modi’s case, and within Bengal, in Mamata’s. In Suvendu’s case, such amplification is foreclosed if he ends up trapped in a battle of Shakti in Bhabanipur or a duel of smriti (memory) in Nandigram. What he needs to do instead is wage a war of bhakti from Nabadwip—leading a powerful kirtan (devotional song) whose congregational rhythm and resonance overwhelms Mamata’s sound and fury.

(Originally published on X Articles on 17 December 2025.)